© 1975 by David Lyman

Originally published in Ski America, the Winter- Spring edition 1975

Tuckermans Ravine . . . The name itself has a foreboding ring. The Ravine, named after some long ago botanist and woodsman, is actuality a glacial cirque, or bowl carved out of the eastern side of Mount Washington, the East’s tallest mountain. Winds pack the snow into this bowl all winter, fifty feet deep, so it lasts into mid summer.

Tuckermans, since the 1930s, has been a ski area. But not a ski area as you know ski areas. Here, there are no lifts, no parking lots, no nightclubs, and no lift tickets . . . hooray! But there’s skiable snow long after the cows I’ve gone to graze on another northern New England hillsides. This is The Spring Skiing Mecca which exists nowhere else. Tuckermans is not only high Alpine mountain corn skiing, Tuckermans is a State of Mind. It’s a vision that begins creeping into the conscientious of all Eastern skiers in late winter. “You going to Tuckermans this spring?” people ask.

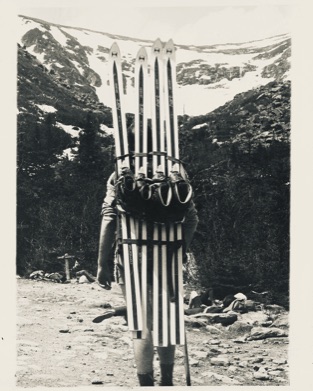

What makes the Ravine “special” is its inaccessibility. You have hiked up 2,000 feet, on the 2.5 mile Tuckerman Trail, caring skis, boots, extra clothing, lunch, perhaps dinner, qualities of assorted liquid refreshment. The climb takes anywhere from an hour to all day depending on the clamber’s physical condition.

Once there, you are faced with the steep Headwall, narrow snow filled gullies on either side, open treeless snow fields, and an ambiance that brings thousands of skiers here each spring.

Tuckerman’s is open in April and May—when the US Forest Service says so.Closed for avalanches the rest of the winter.

You arrive at Howard Johnson’s, the AMC Hut at the base of the Little Headwall. There you rest up, drink, change clothes, and climb into your ski boots. Now, more climbing, with skis over your shoulder, both poles on the other hand, up you go, over the Little Headwall into the bowl. On a good spring weekend, thousands of skiers are here, getting in line, single file, to climb up a series of steps carved into the side of the bowl by the Park Rangers.

When your time comes, you inch out onto a ledge carved into the near vertical bowl face, and go through the process of strapping into your skis. This is the time of the Marker Toe and the rotating, no-releaser heel, with a 3-foot leather thong to wrap around your boot. Behind you a hundred skier are urging you to hurry. You take one look down the bowl face and doubt the sanity of your choice to come here. But the crowd behind you is turning ugly, you place your poles over the edge of the ledge, slide off into a long traverse across the bowl’s face, the uphill ski two feet about the downhill ski. Skiers ahead of you and down slope are managing to carve turns or just, like Tony Matt, letting it go and head straight down. This is “extreme skiing” at its most entertaining. For a few moments every eye is on you. Will he turn, slip, crash, fall, slide all the way to the bottom?

You don’t get more than a few runs in before it’s time to head back down, or camp out for the night.

Races in Tuckermans Ravine

For years Harvard and Dartmouth, rival ski teams, held an annual race on Hillmans highway— a narrow, near vertical shoot on the side of Bootspur, on the south arm of Tuckermans ravine.

A more famous contest in the history of Americans skiing was the American Inferno Race, based on a similar top-to-bottom mountain race in Switzerland. The Inferno, held in the 1930s, was a 5 mile race, a near suicidal plunged that started at to top of Mount Washington, down through the snow fields, then over the lip of the Headwall, straight down, over the Little Headwall, passed the AMC hut, affectionately call Howard Johnson’s, and down the 2 1/2 mile Sherburne Trail to end up at the AMC lodge at Pinkham Notch. The inferno stands as perhaps the longest downhill in America, if not the world, it certainly was the most strenuous and demanding of all races. Racers spent the morning making the four hour climb to the starting gate.

“You never had an opportunity to make a single practice run,” Tony Matt told me in a phone interview recently. “We took it sight unseen.” At the time, 1939, Tony Matt, a 19-year-old instructor from Austria, had been brought over as a “ringer” to represent the Eastern Slope Ski Club in that race. Toni won the Inferno Race, beating the record set the previous year by Dick Durrance, a Dartmouth student. The story Toni told me seems now more of a tall tale, when one considers the soft leather boots, Hickory skis and bear trap bindings used at the time. But race he did.

I spoke with Tony back in 1975 for an article (this article) for Ski America. He was then the head of the ski school at White Face Mountain ski area Lake Placid, New York.

Tony had never even seen Tuckermans Ravine until the day of the race. “On the climb up I wondered what I would do. It was obvious that the racer who could keep his speed on the flat section of the Shelburne Trail, and not have to walk or pole, was going to win,” Tony recalled. “What I had planned on doing was making three or four turns on the headwall then shush the rest of the way to keep up speed. I didn’t quite work out that way.” Tony explained. “Not having ever skied Tuckermans before, I made my turns above the headwall, by the time I started my shush I haven’t even reached the head well, but I didn’t know it at the time. Once I dropped over the head well there wasn’t any sense in turning, because I couldn’t slow down. They say I was going nearly 90 mph. So, I just let it go. I was lucky enough to be in good shape and to stand up. It was fastest I’d ever skied.

The Inferno Race was never the same after Tony Matt’s famous shush. The race was suspended during the War, and enjoyed only a brief rebirth in the post war years. “We try to hold a race in 1958,” said Tony. “They sent applications to every class of racer in the nation. Out of 150 to 200 racers 6 people entered. Of course we didn’t hold it, but we did send out a questionnaire to find out why. No one wanted to race in a big race like the Inferno. The racers felt, since they had to spend half the day climbing up, they couldn’t do their best on the way down. Also the unpredictable weather wouldn’t allow them to train as much, maybe a day or a week at most.”

So the Inferno Race became part of Americans skiing history, along with Hickory skis, bear trap bindings, and racers who thought little of a four hour climb in the morning before a 5 mile downhill race.

“Has spring skiing in Tuckerman’s change much?” I ask Joel White, Assistant Manager at the AMC lodge in Pinkham Notch, embarkation point for all Tuckermans Ravine skiing. “Have you noticed a change in the type of skier during the past 10 years you’ve been here.

“Not really I guess,” he said. “On the positive side everybody has been more cooperative with our “carry in and carry out policy.” We’d started this in 1968. There’s little trash left around now. For the most part skiers and hikers are keeping it clean.” But he did have one gripe with skiers who visit in the spring.

“There is one problem. It’s skiers helping other skiers. We had three accidents here last spring. The volunteer patrol had to call down to the hut for assistance in caring out the injured. With 1500 skiers up there that day, not one was willing to carry a litter, or carry the patrol’s gear, or the injured skier’s gear. We even had skiers complain because they couldn’t pass the rescue crew that was carrying out the injured.”

The Ravine is not an easy place to ski. It’s also dangerous for the unprepared, unskilled and unknowledgeable. The slopes on Mount Washington are the most respected in the world among mountain climbers. The most recent death occurred this past Christmas when a skier fell in the Ravine. A skier was killed in spring of 1973 in a fall in the left gully.

The Mountain attracts unpredictable weather. The skies can fill with clouds and driving snow in a matter of minutes. The highest wind velocity recorded on earth was recorded at the Weather Station atop Mount Washington. The instrument recorded a wind speed of 200 miles an hour plus, before it was blown away. The steepness of the headwall, Hillmans highway and various couloirs and gullies that ring Tuckermans Ravine are a challenging to even the most expert skiers.

“It’s overcoming the fear that the headwall throws into you,” a 35-year-old ski patrolman told me. “That fear gives me one of the biggest kicks in skiing.” But like most ski areas, Tuckermans offer something for the intermediate or even the novice. There’s the run out at the foot the Headwall for the faint of heart, the little head wall for the juniors, there’s a run out down the long winding Sherburne Ski Trail a for the novices. If your ski Tuckermans early enough in the season (it’s usually is not open until April Fools’ Day, due to avalanche danger), you can ski all the way back down to your waiting car and Pinkhams.

Memorial day is traditionally the big day when Canadians come down to celebrate the queen‘s birthday, and upwards of 3000 people can crowd into the Ravine.

"You Headed to Tuck this a spring?"

There are no hotels in the ravine, but there are AMC open shelters, with sleeping bag space for 86 people, the maximum number of the forest service will allow to remain in the ravine overnight. There was a time when hundreds of skiers would be bed down on the ravine floor under spruce, fir and Juniper, but the district manager in Milwaukee (Milwaukee? Yes, Milwaukee) close the door at all at all but sheltered campers.

These lean-to spaces go for $1.50 a night per person and are reserved form the AMC Hut in Pinkham Notch on a first come first serve basis.

“We’ll have over 100 people lined up to get the passes, and when we open at 7 AM,” Joe White told me. “The shelters are generally full, especially on weekends. And you have to be here to get a pass, no calling in for reservations.”

For those unlucky enough not to get a pass, it means hiking or skiing back down that afternoon with the prospect of having to hike back up again the next day. Lodging is available, although limited at the AMC Pinkham Notch Lodge, on Route 16, between Jackson and Gorham, a mile away from Wildcat ski area.

Tips for the Revine bound skier

Go with someone whose been there before. Hike up, in hiking boots, not your ski boots or sneakers. Bring a change of clothes and underwear. You’ll be drench with sweat when you get there. Wet clothing can freeze if spring suddenly turns back to winter. As is often the case.

Carry ample food and water or other suitable beverages. The stream water is clear but not recommended for drinking, although everybody does. Two items you’ll find indispensable: suntan lotion, as the sun is more intense than at the beach in mid summer, and sunglasses, as sun blindness is not uncommon for the unprotected. Check the snow conditions on the board at the AMC lodge before heading up. Keep an eye on the ice that hangs off the rim of the Head Wall and be prepared to move quickly if I starts to fall. Drink lots, because you’ll perspire lots. And leave with sufficient time to get back to Pinkham Notch before dark. Expect a long hard climb in if this is your first trip but once you’ve arrived, you’ll realize why all the fuss. And you’ll know why the Ravine is like no other place on earth. You’ll be back.

Skiing Tuckerman's Ravine:

the ultimate “extreme skiing” experience