The 50th Anniversary

of The Workshops

This summer, 2023, is the 50th summer of The Wokshops in Rockport, Maine.

The followionmg text horiginally appeared in "Workshop Stories," a book edited and designed by Elizabeth Opalenik, published in 2020.

The Maine Photographic Workshops, and The International Film and Television Workshops are two summer schools I launched in 1973 and 1975, respectively. In 1996, The Workshops became a college, and since 2007, the schools have been MaineMedia.edu. The idea of one-week intensive master classes and workshops was an idea I appropriated from The Center of the Eye in Aspen, Colorado, where I attended a workshop in '72. The Maine Workshops consumed 35 years of my life and became an international conservatory for the world's creative storytellers: writers, photographers, filmmakers, and journalists. The idea soon took on a life of its own. I was the stage manager, helping make the magic out front. It was one of my life's greatest adventures.

You can read how the workshop philosophy developed by CLICKING here.

Now the story:

The summer of 1972. While working as a freelance magazine photographer and writer, I discovered a great way to grow my career—a one-week summer workshop.

Being technically competent did not make me a photographer. What I didn’t know was how to see the world as a photographer does. I’d been a Navy Photojournalist in 1967 and when I returned from Vietnam I began looking at the work of other war photographers. I wanted to see how they had photographed their experience. I realized then what I should have seen, but didn’t. I’d been self-taught, working in a vacuum. I had no background in the history of my art form, therefor no context on which to base my work. I had a lot to learn.

I heard about a ten-day photography workshop in Aspen, Colorado. It was one of a series of summer classes held at the Center of The Eye. I went. Spending a week working with a group of my peers was enlightening. I got to see how each of them saw and worked. We were being pushed and mentored by two of the greats in photojournalism: Bob Gilka, Director of Photography at The National Geographic, and Angus McDougall from the University of Missouri. It was humbling. It was transformational. I was so moved by that one-week experience that I went in search of other one-week workshops.

Ansel Adams hosted a workshop in Yosemite National Park for landscape photographers. The National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) held its annual Fall Missouri Workshops, a bootcamp for newspaper photographers. The Professional Photographers of America (PPA) held portrait and wedding workshops in Winona, Wisconsin. Minor White held a workshop in his home in Cambridge. Apirion Workshops in the Catskills held one-week classes for visual poets. Nothing came close to what I had in mind.

If I had only one week each year, I thought, where would I go? Someplace away from my normal life. A place where I would be surrounded by other photographers. I wanted to be wrapped up in the process of being a photographer. What would that place look like?

I started The Main Photographic Workshops the following summer.

Finding a Place

January 1973, I drove over to the Maine Coast to scout a location. I’d explored much of the coast on my sailboat, so headed for Camden. This a resort harbor village, not unlike Aspen, smaller, but more accessible. Route One winds through town. There is bus service from Boston. An airport was 15 minutes away. It was rural, other-worldly, maybe from another time. There was the sea, the landscape, farms, forests, mountain, lake, rivers, and small towns. Lots to photograph. Even the residents were different.

Someone suggested I explore Rockport Harbor, a village "just over the hill.”

“It’s practically a ghosts town,” they said

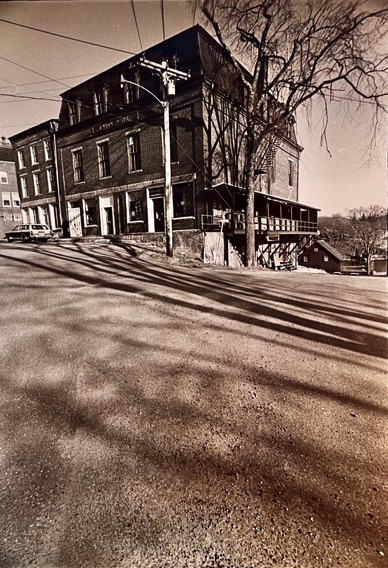

I drove over and found this one street village, peached on a hill above the narrow harbor. It was perfect. There, in the middle of the village, was a four-story brick building, Union Hall. The Post Office occupied half of the street level, the second floor was the abandoned town hall, and the third floor was a vacant warehouse. The vacant basement, except for two cars, was what interested me.

I rummaged around in the dark and dusty space for two hours, pacing off the dimensions and drawing up a floor plan. The space once housed a cooperage and a barrel-making shop; some of the machinery was still bolted to the ceiling rafters. The doors opened onto a side street that ran down the hill to the harbor. Great view.

I found the owner, Luke Allen, just down the hill and offered him $1,000 for summer rent. He agreed. I now had a space for darkrooms, film processing sinks, and a wall on which to pin up faculty and student work. The Maine Photographic Workshops had a summer home. Next, I went in search of a faculty members.

Who Will Teach Here

The first person I invited to lead a one-week workshops, was Dick Durrance, staff photographer at the The National Geographic Magazine. I’d met Dick in Aspen that previous summer when he gave our class a slide lecture on his career and work method. It was enlightening. He agreed to come. I invited two LIFE Magazine photographers John Dominos and John Loengard. They said yes. Laurie Riley, a photographer friend put me in touch with Arnold Gassen, head of Ohio University’s graduate photo program. He agreed to not only to come, but to spend the summer. He brought along a few of his grad students to help out. Charles Harbutt, another magazine photographer came and for many summers lead a class called ”Learning To See.” NYC fashion photographer, Bill Silano, led a fashion class. Bill Hayward, who led the photo department at Castelon College came. I asked the landscape photographer Paul Caponigro to lead a master class. He came and now lives nearby.

Tuition that first summer was $180 for a week, with a $15 lab fee. Accommodations in town were $30 a week. Enrollment was limited to no more than 12 per class—we seldom reached that. Portfolios were required for acceptance into master classes. This stipulation not only ensured that those in a particular class were all on the same page technically, but it also lent an air of seriousness to there operation.

I took out small classified ads in The Atlantic and PopPhoto. Laurie’s husband, a graphic designer, came up with a logo and a poster, which I put up in camera stores, and on college campuses. Enrollment trickled in, enough go ahead.

Building The Place

That May of 1973, I begin work on turning the abandoned basement cooperage shop into a photography center. If you have a good idea, share it. People came out of the woodwork to help. Two Maine carpenters helped me partition off the basement. We built a large gang darkroom, an office, a store, a gallery, a classroom. I paid them with free workshops. We built a 10-foot long film processing sink, and added two film loading closets. We build counters along the walls in the gang darkrooms and added a 4 x 8 plywood sink using fiberglass. I’d talked Saunders Photographic in Woodside, LI to loaning me 30 Omega enlargers for the summer. I’d sell as many as I could at a discount, and return the rest. We sold all by 10.

George and Laurie Riley arrived a few days before the students to help solder together the plumbing for the sinks. We opened on time.

We had 150 students that summer of 1973. I lost $10,000. I went back to freelancing, earned back the loss, and rolled the dice on a second summer.

What Can This Place Be?

In the second summer of 1974, with more workshops, the enrollment doubled. I still lost $10,000. I was not learning much about being a photographer, but I was learning what this place wanted to be. In the 34 years I ran the place, I never got to take a workshop.

So, while the place was expanding, buildings were rented, then bought, and then designed and built on a ten-acre campus, a ten-minute walk from the harbor. So too was the philosophy—how we taught technology, methodology, workflow, and aesthetics. We developed a way to critique each student's work and structured each class so it could be "transformational? for each student. We were inventing and perfecting "The Workshop Experience." I wrote a book to help new faculty members, those who had never led workshops before, design their classes to be meaningful and successful.

By the end of the third summer of 1975, I realized we might turn a profit. I made a calculated gamble. I bought Union Hall, along with a seven-bedroom Victoria house in which to house students. It was a financial stretch, but my folks, the bank, and the property owners themselves all came together to make it happen.

A Film School?

That same summer, 1975, I had invited Academy Award-winning cinematographer Conrad Hall, ASC to lead a master class in cinematography. Enrollment was a whopping 80 filmmakers in one class. We adding filmmaking, broadcast journalism, acting, directing, script writing, editing, producing, documentaries, Steadicam and film cameras. The Workshops was now a major player in film and broadcast journalism.

A Year-round School?

That same summer, 1975, two of my summer-long faculty, Craig Stevens and Richard Procopio, told me they weren’t leaving in the fall.

"You need to offer a year-round photography program," they told me. We had a dozen students that fall and winter. A wood stove outside the gang darkroom our only source of heat. That year-round program developed into a Professional Certificate program. This led to a ten-year partnership with the University of Maine at Augusta. This morphed into an undergraduate and MFA degree program when the State of Maine certified The Workshops in 1996 to confer degrees as Rockport College.

When we concluded that first 14-week Resident Program in 1975, we held a one day exhibition of student work in New York City. I’d talked Cornell Cappa, ICP’s Founder, into to letting us clear out a corner basement storage room, fix and paint the walls, and hang a one day show. More than 100 people showed up. We took the work down that evening. From then on, The Workshops had a presence in NYC every fall. The Annual Fall Show turned into the Golden Light Awards with exhibitions each fall at the PhotoPlus Trade Show in NYC.

Going Abroad

In the late 1970s, Kate Carter and I were invited to the Rencontres, a photo festival in Arles, a city in the South of France. This annual events draws thousands of picture people from all over Europe. I thought, why didn’t we have anything like this the States? Five years later, we did when The Workshops hosted The International Photography Congress.

By the mid 1980s, instead of offering 15 workshops a summer, we were holding 20 workshops each week. Our YoFo and YoFi high school workshops were packed with 80-teens on campus. Enrollment grew to 2,500 students a year. Our annual budget grew to over $5 million. The Workshops had become what I’d dreamt of ten years earlier, a place and a time where creative people could live, work and play together making images and storytelling for a week or two. We hung exhibits in the gallery, built an extensive library of photography books, held lectures by visiting masters in the evenings. Everyone sat down together for meals under dining tent. Each week a dozen famous visuals artists were in residence leading master classes. Students were making photographs, writing stories, shooting and editing video. Each morning their creative work went through honest and in-depth critiques. Then, more work in the afternoon. Non-stop, creative energy filled the air. On Friday, after a lobster dinner (this is Maine after all), the Wrap Party showcased what each class had created that week. It was exhausting. It was thrilling.

The International

Photography Congress

That idea of a festival got off the ground in 1985. Nikon sponsored the first The International Photography Congress at The Workshops. Rockport, even Camden, being too small to replicate the Rencontres, Congress took on its own mission . . . to bring together the movers and shakers in photography for a week of presentations, debates, conversations, panel discussion, and elbow-rubbing. Kodak came in with bigger bucks and Congress began to wag the dog. In the summer of 1989, John Scully, CEO at Apple made a presentation with Russel Brown from Adobe. They showed what Photoshop could do on the tiny Macintosh. Ray DeMoulin, Kodak’s VP and The Workshops major sponsor, brought a few of the inventors at Kodak Park to show what they were developing. When the Apple boys saw what the others was working on, someone said: “Can you plug that Nikon F camera with a scanning chip on the pressure plate into the back of this Mac so we can see what your camera is seeing . . .” Digital Photography became a reality that day.

Community of Peers

The Rockport workshop experience, I soon realized, was not just for the students. The visiting faculty demanded their own peer group as well. Mary Ellen Mark, Arnold Newman, and others would call to ask who would be here the same week as their class. On Thursday evenings, while the students were in the darkrooms and editing suites preparing for their final critiques on Friday, the faculty gathered at my lake cottage for a private barbecue. The conversations went on until midnight.

A Research Center for Creativity

The Workshops had become my personal laboratory. I listened to what students wanted, what the visiting faculty suggested. I came to understand how creative people learn and grow. I watch students struggle with the technology, attempting to release their inner artist. I saw the roller coaster each student went through each week. Mid-week became BMW Day, Bitch and Moan Wednesday. Everyone is frustrated, over worked, ready to throw in the towel and head home. No one does. By Thursday, most see what has been happening to them. It’s non-intellectual. The only rational explanation, is that taking a risk, pushing past our current comfort zone, is the only way to grow as an artist.

“This week I am giving you permission to fail.” I would tell each new class on Sunday evening. “No one is going to fire you if you make a mistake. In fact failure is applauded here. If you screw up, don’t say it’s a mistake. Call it an essay, an attempt, a trial, an exercise, anything but a mistake. Then it becomes just part of the learning process.”

By Thursday, flash bulbs were going off. People began to discover something about their talents, limits, and potential. They discovered a better way to work—to use the creative process. They acquired mastery over the technology and learned to understand methodology, history, and where their talents might lead them.

Building The Workshops became my mission in life

But, I did not do this alone. The students, the faculty, my staff, and even the sponsors helped me realize what this dream wanted to be. By now, the place had taken on a life of its own. It had pushed my original vision further. I was now the stage manager behind the curtain, making magic happen out front. The workshops became the place I'd always wanted to attend, a place where creativity, risk, hard work, and having fun helped people discover and release their creative potential.

The End of an Era

In 2007, after 34 years of helping The Workshops grow, I turned my schools over to Maine Media, a nonprofit board of alumni and faculty. A land developer, Lucadia, came in, paid off my $3.5 million debt with the bank and acquired by assets. I was free. I took the family and sailed to the Caribbean for a year. Today, we live in Camden. Looking back at this creative life, I’m back writing for magazines and working on a series of memoirs.

David H. Lyman

Camden, Maine

May 2020

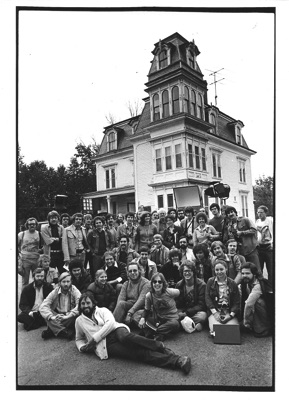

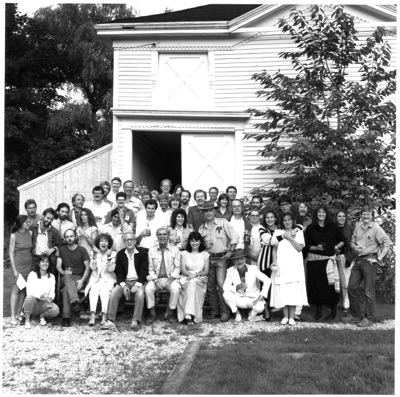

The Workshops' Summer Staff, 1998 - wel;, most of us.

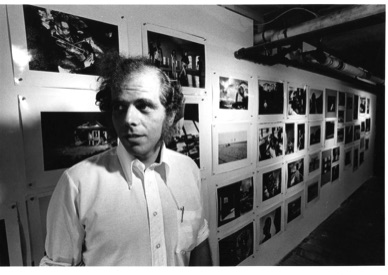

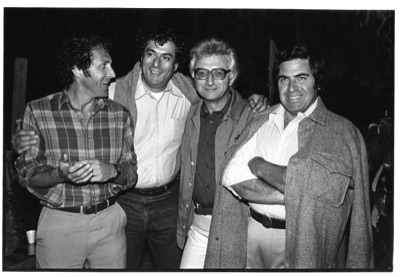

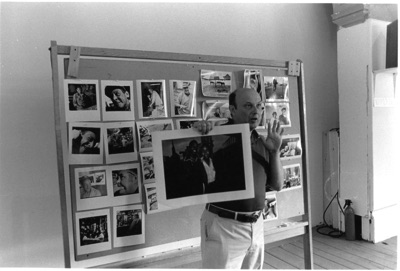

John Loengard and a gallery of his photographs. Below: Dick Durrance, Ben Fernandez, Lucxien Clergue, Paul Caponigro

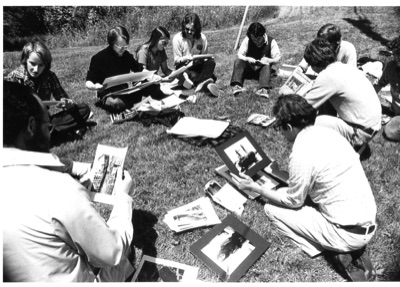

Bruce Davidson shows his master class his work.