Fritz Stammburger

Profile: A World Class Mountaineer

I wrote this article in 1974 for The Student Skier magazine. I’d met Fritz in Aspen that previous summer while attending a picture story workshop with Bob Gilka, Director of Photography at the National Geographic. Fritz was to be the subject of my photography assignment that week.

What I wrote is a better picture of Fritz than the photographs I took that week.

It was Sally Barlow, friend, Aspen resident, and reporter for the Aspen Times, who introduced me to Fritz. He ran a commercial printing shop at the back of the Times building.

This was the same Stammburger whose accomplishments I’d read about in mountaineering journals. The same Stammburger who became an outspoken opponent of rampant developing an Aspen and the planned development of Haystack Mountain nearby. This was the same Stammburger who hoisted himself into a tree in Aspen, tent, food, books and all, vowing to remain there until the tree’s owner agreed not to cut it down. This was the same Stammburger, you could see riding around Aspen a unicycle. A fascinating man indeed.

It was a warm July evening that summer of 1972. A group of us were leaving the concert tent on the grounds of the Aspen Music Festival when I finally got to meet Fritz Stammburger. My date, Sally Barlow, introduced us and he suggested we all stopped refreshment at the Ute City Bank on our way home.

The Bank is no longer a bank but a new restaurant and bar, smack-dab in the middle of town. In all appearances, it is nothing more than a bank, externally as well as inside. The exterior is brick, the interior woodwork is intricate and excellently done. The booths are former tellers boxes. The walk-in vault now frames the bartender. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would not have been out of place in the next booth.

Tourist, residents and musicians from the just ended concert were beginning to fill the bars we arrived. Fritz, obviously will recognized about town, had a little trouble procuring a booth for the party. One of our group with a terrible thirst, ordered a beer with ice cubes. Fritz hit the high vaulted roof.

“These Americans! They have no taste!” he raged in the tone of German superiority. “What do you want to ruin good beer for? The beer is bad enough without putting more water in it!

“But . . . I want something very cold,” came the defense.

“That’s the trouble with Americans. You people always looking for oral gratification. Drinking cold beer never any any taste. Beer is not supposed to feel good. It’s supposed to taste good. That’s another reason Americans are overweight. You eat and drink, not because you’re hungry or thirsty because it feels good.” Fritz continued his rant on American culture, entertaining us all for the remainder of the evening. Fritz, I quickly learned was quick to point out any fault, and something to say about nearly everything. I later learned, many, if not most, of his ideas bore some weight and we’re worth listening to – – which as it turned out, it was what I’m was to spent the next two weeks in Aspen doing– listening to Fritz expound on a number of subjects.

I learned that Fritz is something of a snob. Not everyone will immediately like fritz, as I did, and the converse is most definitely true. When a man’s life has been centered on accomplishments and deeds, he isn’t about to waste time on braggers, blowhards and “turkeys” as he is often calls tourists who pack Aspen in the winter.

That following day I met Fritz in his print shop behind the Aspen Times and we began a regular afternoon ritual . . . tea. It was usually at the Epicure, a small café a block from The Times, with an outdoor patio which was quiet, shaded and which served excellent tea in a variety of cookies, a delight for Fritz. Tea, it seemed was an event, a daily occurrence with Fritz, one which demanded a major catastrophe to be postponed. It came, he told me, from being raised partly by an English couple while he was a kid in Tibet. Tea, as we all will know, it’s a rule English life. I found a daily practice stimulating and began to look forward to each meeting.

It was during these afternoon social hours I got to know Fritz better, and be soon became fast friends. But a bit of background before we go.

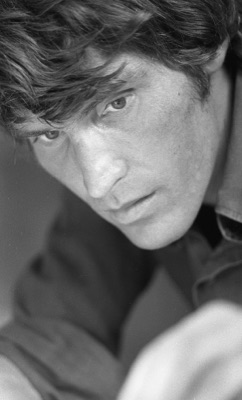

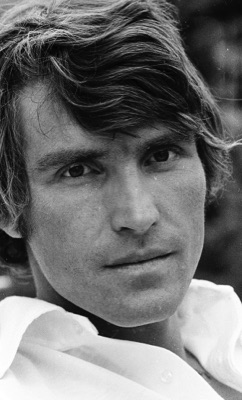

By trade, Fritz is a Master Printer, having gone through years of apprenticeship in his native Munich. He owned and runs Printed-in-Aspen, a small but active print shop. He also is the publisher of Climbing, a slick magazine for serious mountain climbers. He authored a book on climbing, which has been published in Germany, and occasionally teaches skiing, the trade which brought him to Aspen a couple years ago. Fritz has just turned 30, a few years younger than me. He looks younger. He’s impressive in stature— strongly built, over 6‘2“ tall, with a fine Aryan face and floppy black hair. His accent is German, but he has an uncanny command of English and an extensive vocabulary.

He’s recently divorced, and shares the raising of their young son Anton with his ex-wife and a mutual friend, but back to our story.

Maroon Bell is a series of sharp peaks west of Aspen there’s always stood as a challenge to amateur climbers, such as myself. Aspen friends told me the climb was hard, but not overly long, and the Fritz, of all the people in town would be the best guide. I asked him about the climb, the length, the necessary equipment and found a ready and willing guide. We set a date for the following Sunday. It was an afternoon climb to just below the summit, camping out overnight, then climb to the summit on Monday morning and return to Aspen by 10 AM the same morning. I was anxious about the climb for three days is I broken a new pair of climbing boots.

As luck would have it, we got a late start. Sally, Fritz‘s new girlfriend came along: my boots soon develop blisters on my heels and we cut the climb short as darkness fell at the foot of the bells. It was a pleasant trip nevertheless, as we talked over a small campfire next to maroon lake. Had soup from Fritz’s of supply of experimental high-altitude foods, along with tea, granola and some spam and cheese which I brought, providing us with supper as we finished our last two beers.

The morning dawned early and cold at 10,000 feet. Sally was up first fussing with the fire and breakfast was soon out-of-the-way. Fritz and Sally shoulder packs and headed back to Aspen, well I now in my boots headed off up the screefield to attempt a climb to snow fields of South Bells It was a pleasant morning, and I was full of wonderment at the grandeur of the place, the intricacies of geology, the perfusion of wildflowers. It was slow going as I was pausing frequently to photograph. I got as far as the chutes, or couloirs, where the climb became a challenge. Patch of soft snow and occasional ice. Deep down under the ice I could hear a mad river rushing over rocks and hidden falls. The winter snow was melting.

It was noon when I reach a ledge where I could sit, removed my backpack, unlaced and removed my boots. The heels of booth feet were raw. I sat, ate lunch and gazed out at the mountains.

Here in Colorado the geology is dramatic. Two continental shelves crashing together, throwing up three mile high waves of rock. Ice and glaciers grinding down rock to reveal layers of sediment and volcanic action to create valleys with the rushing waters of snow melt, eroding the mountains. Back East, our mountains are soft and rolly, warn down eons ago by the ice age. It’s worth the expense, time, hassle and difficulties, just to sit here and see this. I thought of about Fritz and what he’d been talking about during the week, sitting comfortably and unconcerned back in town at the Epicure.

Fritz has made the mountains part of his life. Each spring when the sun returns to the Himalayas, he returns to the mountains on a 4 to 10 week expedition. This isn’t a vacation or adventures excursion, Fritz is working on a project. He told me about the project three days earlier.

Stammberger is out to prove that men can climb all known peaks—without the use of a supplemental oxygen supply. It’s a goal he feels he can achieve. Here I was, sitting on a ledge halfway up Maroon Bell, at just 12,000 feet and I’m gasping from a lack of oxygen. I could appreciate the task ahead.

This man is at war with himself, I thought. I can see this in particular everything he does. He’s like a young boy with new toys. These toys are his body and his mental capabilities. So far he’s not reached a breaking point of either. Last year, he drove his body for eight days, lost in a blinding blizzard in the Himalayas.

“It can be done,” he told me over tea one afternoon. “I’m sure of it. It’s all a matter of conditioning. I’m sure the body can function of that attitude; it’s the mind that must drive the body.” Fritz was speaking of an unthinkable goal—even in today’s climbing circles—the conquest of Everest without the use of oxygen tanks. “I’ve already been to 26,500 feet without using oxygen,” he said as we drink tea. The noise of Aspen’s busy street outside the café were surreral. “Everest is 29,000 feet. With good weather, I can do it.”

A Typical Everest Summit Trek, if there is such a trek, involves three full weeks of acclimatization at 15,000 feet base camp. The Climb from there to the 26,000 foot summit takes ten days. Fritz lives in Aspen at 8,000 feet, with frequent trips into the high mountains to 15,000 to maintain his high altitude training.

Has he got it together yet? Not quite. Following an expedition to the Himalayas a couple years ago, he returned with severe mental stress, having ascended to 23,000 feet without acclimatization. Returning home, he was plagued with a recurring “trips.” He suffered from visual and acoustic disturbances. “The world sounded if someone was fooling with the balance controls on my stereo. I got cold sweats frequently. Peoples faces around me with disappear, drop out like in a movie.”

The effects of a lack of oxygen on a brain, accustom to living at a lower altitude, proves that high-altitude climbing has its problems. “23,000 feet is nothing special,” he tells me. “I’ve been to 26,800 feet, but to go higher without the body getting used to his bad. The Sherpas with me on both climbs we’re not bothered excessively by the lack of oxygen tank. I really feel it can be done.”

“If I can prove that the human body can adapt and function at high altitude and climb a peek like Everest, then I shall declare all peaks climb with use of oxygen invalid.”

A thunderstorm at the east end of the valley ended my reverie, and I hurriedly packed and shouldered my burden for the scramble down the side of South Bell. It was raining as I reach the valley floor 90 minutes later to began a slow hike to main highway hoping to catch a ride back to Aspen for dinner.

Life with Fritz is not normal. A few days later we met and organized a double date for that evening. Sally and I met Fritz and his Sally at the entrance of the music tent to take in an afternoon concert. This was followed by quick climb up of Shadow Peak, a sharp rock spine that raised up from the edge of town to watch sunset. It was seven in the evening but the girls seem excited about the exercise. We scrambled over the tailings of the many silver mines that honeycomb Ajax Mountain and reached to Point high above town, just as the sun was disappearing on the buildings below. Then, the uniqueness of the situation struck me. What could be more natural, the sun sitting behind Aspen Highlands as we returning to civilization. Only few moments ago, Aspen appeared like a toy town below us. We spent the remainder of the evening at Fritz’s condo listening to records and snacking on junk food and wine.

“Is it your goal to prove to climb Everest un-aided by oxygen?” I asked him the next afternoon over tea. “Do you. Have a desire to rid climbing of the technology and machines of modern mountaineering?”

“No,” he said. “It would be a little foolish to get rid of the technology. But I think to rid ourselves of all technology which imprisons us, which diminishes the quality of life, is a better way of saying it.”

“An example please.”

“Let me see. Say you’re going to climb El Capitan. You might say to yourself . . . ‘Ah,ah . . . if I do it, it’ll all be in the papers.’ Of course you may have used 6000 bolts on the climb. Then there is the fellow who goes off and climbs somewhere alone, where nobody sees, no one knows what he did, that is a lasting substance.”

To climb with oxygen, bolts, and another artificial aids,” as Fritz puts it, is not a valid test of self. “You may as well put a ladder up the side of a mountain and walk up. The real test is to do it by yourself.”

Fritz seems to indicate that there may be more to climbing than nearly getting to the top. “Many of the climbs are made to catch the public attention, to capitalize on the glamour of the climb,” he said. “That type of climb is short-lived. The climber himself knows when he’s cheated. He knows when he has used a machine instead of himself and his skills. If you’re going to climb with artificial leads, why not take a helicopter the top. The view is the same.”

How do you prepare yourself for a climb in which you eliminate many of the usual aids?

“It’s simple. Conditioning and discipline,” he said in his Bavarian laced English, “which has to be motivated by inspiration. And that, my friend, is what I have been meditating and thinking about. What is inspiration? It’s hard to find. How in one second can we be so weak and the next second, so strong. Suddenly we have energy to burn. Fear is not inspiration. Fear is different. It’s a negative reaction, a protective reaction. Fear only keeps us alive. Inspiration keeps us going on toward goals that make a difference in how we live our lives.”

Is inspiration divine? I ask. Does inspiration come from a spiritual source? In the early 14th century, a the word “inspire” aluded to a divine influence upon a person, from a divine entity. It literally means to breath in, to take in.

“I don’t know. . . . Not yet. Ask me in two years,” he said. “These are the things I think about when I’m alone, hiking.” A thoughtful waitress brought more tea and Fritz ordered more cookies.

“If I had to state a direction in my life,” he continued. “I’d have to say it was backwards, toward not using technology. It’s a cliché I know, but I would say it’s back to nature.”

Would you get rid of your silver Porsche, I asked. Isn’t that the car of your dreams as an adolescence in Germany?

“Sure I would,” he said in emphatically. “If the public transportation here was adequate. I’d get rid of it immediately.

Why not own a VW then, I asked. It’s cheaper and just as good transportation.

“I’d go crazy in a Volkswagen, driving to Denver. I can’t stand being cooped up. Unless there’s some compensation like the exhilaration of driving fast. The Porsche becomes a part of me, and extension, like my skis.”

Then you get a thrill out of speed. Do you ski fast?

“Yes I guess I do. What does Freud say? It’s a sexual gratification, a male gratification. I like speed and I guess I ski pretty fast too.”

Speed is danger. Is it the danger that thrills you? You climb and that’s dangerous. You put yourself in a position where death is always a possibility. Why?

“I must say I like that. I like the death thing. But the odds have got to be pretty good.”

But the odds are with you? Right? You and good equipment. A good car, good skis, reliable climbing gear. You wouldn’t drive as fast in a jeep would you, or ski and rotten equipment.

“No! But, I will put up with a very remote factor . . . . call it Factor X. There is, despite good breaks, good steering, good tires on my car and the fact that I’m awake and everything is OK, there is still that one Factor X. A deer may jump out in front of the car. That one factor is the price I’m willing to pay. The rest is, I hope all a calculated risk. I’ll take this chance in exchange for this exhilaration of speed. It’s the same way with skiing.”

How about climbing. Is it all a calculated risk for you? You skied the Bells last year. In less than great conditions.

“During the descent, I’m much too involved to evaluate the price,” he says. Then pauses to think. “I knew there was a price and that it would be chancy, but I was cool about it. I’d do it over again. I don’t think it was a foolish decision.

Of all the challenges that Fritz has faced, there is still one eludes him. The first trans-Antarctic expedition, by foot, unaided. To Fritz, it is the last frontier on earth for the individual men.

“It has never been attempted to date. I’ve spent months on the ice studying the weather, typography, possible roots. Becoming familiar with the hardships.”

Teams of men, with dogs and sleds have made it to the Pole, but Fritz is talking about tracking about cross the entire Antarctic, ice covered continent, by himself, on foot, no dogs, carrying everything he’ll need. It nearly 1,000 miles. If he could walk 10 hours aday, at 4 miles an hour, that’s 40 miles in 24 hours. It would take him a month to walk across Antarctica.

“The greatest obstacle is food.” Fritz leans forward on the table, his face close to mine. “It’s the most in hospitable and desolate piece of real estate on earth. Even in the southern summer. Food and inspiration. If I can solve those problems, it can be done.

I could see he was inspired, if not by the fame it would bring, he already had more of that than any man’s deserved, fame or notorary. But the food issue, that’s the problem.

“How can I carry enough food on my back to sustain me for 30 to 40 days? The time it will take to make the trip. If I carry freeze dried food, that means I have to carry fuel to melt snow for water to reconstitute the dry food. I tried stuffing my body with food, instead of my backpack on my last expedition into Tibet. It didn’t work. It took more calories to carry those extra fat cells around then if I’d carried the food on my back. There’s no getting around it. You just have to have so many calories a day. The problem seems to be self-defeating.

Then, there’s no ready answer with today’s foods.

“No, I still think there must be an answer somewhere. In my last expedition to the Himalayas I watched how the Sherrpas and porters eat, and what they ate. They had a little bit of crude oatmeal each day. Water they drank later. They all had legs as skinny as my wrist and yet they carry more than I do. I don’t know how they do it. Maybe it’s the inspiration of the six rupees on paying them that keeps him going. I don’t know, but if they can do it so can I.”

I was not convinced Fritz would last long on crude oatmeal. Over dinner one night at the Chart House, Fritz shared his thoughts on food with us at the table. As evidenced by his eating habits, Fritz is a lover of food and appreciate both of substance preparation and manor of presentation.

“I’m not a gourmet. I would have to say I’m almost a cultist when it comes to food.” He’s been known to devour two boxes of animal crackers while climbing, or to existed for three months in the Himalayas with nothing but oatmeal goat cheese and brown sugar.

“One of the positive part of civilization,” he began. “Is proper dining habits. I mean tablecloths, fine silver and Crystal. Breaking bread with friends should be an “occasion” in each day. That’s what ‘company’ means in Latin—breaking bread. Good company with every meal is important.”

What are you going to learn from transiting the Antarctic? I ask.

“Just that it can be done? As man grows older his horizons bring new challenges. The Matterhorn was once unconquerable. Now old ladies take a Sunday hike to the summit. The Antarctic is the last physical test.

“Can it be done?” He asks himself. “Should it be done?

Why do we climb mountains? I ask.

Sir Edmund Hillary said, ‘because it’s there.’ That may sound like an easy answer, but it really is the answer. Apparently man has to prove something to himself and that’s the point. This, transiting the ice, is a point that I feel it’s possible to prove.

In the doing of it, Fritz will prove, to himself first, then to the world, that he was correct in his assessment of the challenge. He was correct in the planning, the logistics, and his assessment of the risks involved in the physical and mental demand such an expedition extract from each participant. If the journey is successful, that itself will be reward enough. If Fritz fails, besides the personal failure, death will meet him on the trail.

Side Bar

Fritz’s Challenge

Fritz never got to prove his assumption that a solo track a cross Antarctica, on foot, was possible. That fell to the American Colin O'Brady, 33, in December 2018. He covered the final 77.54 miles of the 921-mile journey with one final sleepless, 32-hour burst of energy. Fritz would have been pleased, if not jealous. Colin becoming the first person to traverse Antarctica, from coast to coast, solo, on foot, unsupported and unaided by wind. Ten years earlier, in 1996-97, Borge Ousland was the first to make the traverse, on foot, but he was aided by a kite that pulled him along the ice faster than he could walk.

The secrete that eluded Fritz was the use of a sled, pulled along behind, carrying food, fuel, a tent, and equipment. But would have Fritz considered the sled cheating?

=========

Wrapped Up

It was Sunday, my last full day in Aspen. Fritz called, suggesting we make a quick climb that afternoon. “It’s just the thing to send this journalist back home to flat New England,” he said on the phone. He pick me up in the silver Porsche around three in the afternoon and drove like a crazy man up to Independence Pass, scaring the bejessus out of me. We came to a screeching stop in a gravel parking lot at 12,000 feet. A sheer rock wall faced us.

“That should prove a good climb,” he said, slapped on a helmet, hitched a web belt around his waist, from which dangled and clanged a collection of climbing hardware: bolts, ‘beaners, wedges. He threw two length of colored braided climbing ropes over each shoulder and was off. I followed.

I’m not a stranger to rock climbing, boldering and and hanging off a cliff. I’ve been messing about in the mountains since I was 5, but it’s not the driving passion that possess Fritz. Up he want, finding hand and foot holds where I saw nothing but sheer rock face. Up I want, tied-in to the rope Fritz has secured to face with pitons, removing them as I went.

The climb was not really memorable. I have no written notes to bring back of the experience. But I do have one photograph of Fritz as we were about to climb the wall. I sent him a print. When I was in Aspen that next winter, staying with Fritz. There on the table beside the coach in his condo was my portrait, framed.

I never saw Fritz after that winter. We was lost on a solo trek in Pakistan that summer (1975) in an attempt to climb Trich Mir, the highest peak in the Hindi Kush. Sally wrote me, saying the Times used my portrait of him on the front page announcing his disappearance.

Left over

Fritz, as a single man, has added to the sum total of men’s accomplishments. He is a person, an individual and a thinking being, ever asking, ever searching and he is coming up with some new answers.

4,365 words