It’s 0730 and at least four boats are heading north, out of the harbor.

Why?

I know why.

It’s too damn rolly in here. I’ve known this since last night. I, too, have got to get out of this place.

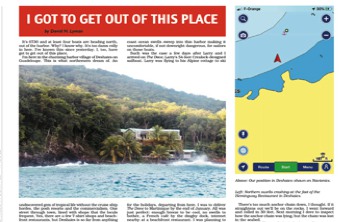

I’m here in the charming harbor village of Deshaies on Guadeloupe. This is what northerners dream of. An undiscovered gem of tropical life without the cruise ship hordes, the posh resorts and the commercialism. One street through town, lined with shops that the locals frequent. Yes, there are a few T-shirt shops and beach-front restaurants, but Deshaies is so far from anything else on Guadeloupe that most tourists have ignored it. Those I do meet come by boat — their own boats.

Deshaies is a small harbor at the northwest tip of this French département. The food is great and the mountainous landscape inspiring, but the holding ground in the harbor is poor. The wind can blow like hell and if there’s a storm lashing the New England coast ocean swells sweep into this harbor making it uncomfortable, if not downright dangerous, for sailors on those boats.

Such was the case a few days after Larry and I arrived on The Dove, Larry’s 54-foot Crealock-designed sailboat. Larry was flying to his Alpine cottage to skI for the holidays, departing from here. I was to deliver The Dove to Martinique by the end of January. All was just perfect: enough breeze to be cool, no swells to bother, a French café by the dinghy dock, internet nearby at a beachfront restaurant. I was planning to stay a week to explore the village and jungle, but events conspired otherwise.

Thursday night I was back aboard, after dropping Larry at the airport and returning the rental car. But something was not right. The sound of crashing waves in the rocky outcrop a stone’s throw from The Dove’s stern was keeping me awake — as much from worry as from the racket.

There’s too much anchor chain down, I thought. If it straightens out we’ll be on the rocks. I went forward and rolled in 30 feet. Next morning I dove to inspect how the anchor chain was lying, but the chain was lost in the seabed.

More worry. The swells had the boat rolling, it was difficult to walk below or board the dinghy. Ashore, I worried. I kept looking to sea to ensure that The Dove was still where I left her. I was not having fun. I was too concerned to enjoy this charming French-Caribbean seaside village.

Breakfast was a banana and a granola bar, then a quick trip ashore. First to the beachside restaurant. It wasn’t open, but the internet was working. I logged on to Windy.com to learn that the wind between here and Antigua today would be northeast, ten to 12 knots. Swells to continue. The northeast wind is doable, motorsailing all the way I could be back in Antigua tonight. Monday would be better with an east wind, but I couldn’t wait two more days.

I decided to go. I’d be a nervous wreck if I didn’t, but I had three major, and very dangerous things to do first.

I signed off after checking e-mail, visited a few shops for veggies, fruit, chicken parts and bread. I stopped at Le Pelican, a colorful gift shop that doubles as the French Customs office, filled in the online clearance paper work, paid the four Euro fee, and was free to leave France. The swells were crashing ashore along the beach, sending spray up the steps to the dinghy dock.

Got to get out of here.

Getting the groceries and my iPad bag onboard with the The Dove rolling is my first test in timing and agility. Agility? In three days I’ll be turning 80 — I should be hobbling around a nursing home with a walker, not monkeying around on a yacht in a strange harbor.

Done. I’m sweating and my mouth is dry. I’m living on the edge. Isn’t that why we go to sea on boats? For the excitement. Then the excitement turns to dread.

Ready the boat. Hatches closed and dogged. Deck ready. Tools handy. Lines ready. Pull the dinghy along-side to haul on deck. This is usually a two-person job. I’m alone. The halyard clipped to the lifting straps, I climb on deck. Crank up the dink to let it drain. Set up my GoPro to record what I know will be a harrowing process.

Up comes dink, only to swing out as the boat rolls in a swell and come crashing back. Luckily she’s an inflatable and bounces off the topsides. Crank. Bang. Hoist. Then she comes flying over the lifelines and across the deck. I narrowly avoid being batted off the boat into the sea. She flies back out over the water as the boat rolls again.

More fudging and dancing. The dinghy painter on one hand, the lifting halyard in the other, trying to time the dinghy’s gyrations so I can drop her to the deck into her chocks. Not working. I’m the ringmaster in a circus trying to control a berserk five-ton elephant.

Finally, done. The dinghy is in place and I’m still standing on the deck, relieved but surprised.

Next harrowing adventure. Remove the bloody sailcover on the boom. This entails climbing up the mast on the winches to remove the top strap, a ticklish trick on a stationary boat, but life threatening when you’re hanging onto a swaying mast. My mind is on my safety. From my mountaineering escapades I recite the climber’s mantra: “three fixed, one working.” That means two feet and one hand, firmly planted, while one hand goes in search of the next handhold. At this height above the deck the arc of swing is increased. I hold on, tug at the strap. I’ve got to do this all with one hand. The other one is for me. Done.

I climb on top of the boom, eight feet above the deck, 15 feet above the sea, to unzip the Velcro that holds the cover around the lazy jacks, and roll up the cover. Normally it’s a two-person job, and I’m sweating and swearing.

Off comes the cover. I bundle it up and throw it below. No time or inclination to fold it properly. I’m left standing there, surprised again.

If I do fall off, there will be no way to get back on the boat. The topsides are too high, as is the stern swim platform, and there is no one else on board. I brought this to Larry’s attention a few days earlier.

“Don’t fall off,” was his solution.

Sail cover off and thrown below, aft sun awning off and thrown below. Nav instruments on, AIS, GPS, autohelm, windless, chart plotter, all on. I enter a way- point into the Navionics App on my iPhone for Five Islands Bay on Antigua, where my family plans to join me for Christmas. It’s open enough to enter at night, it’s 47 miles distant: eight hours at six knots.

Engine starts. Water exiting the exhaust. Go forward to the windless. In comes the chain, off comes the snubbing shackle and line. More chain. Scoot below to the chain locker to arrange the chain so it doesn’t get tangled. More chain comes in, another inspection below. The windlass winds in all the chain, then the anchor comes up over the roller and is secure. Scoot back to the helm, engine in gear, spin the wheel and head out of this delightful harbor.

It’s noon. I’m still shaking, but greatly relieved to be heading out into the safety of the open ocean. I make a note in my journal. “Christ! Is it good to be back out at sea again.

I Got to Get Out of This Place

Story and Photos by David H. Lyman

This story appeared in February 2020 edition of

Caeribbean Compass magazine

Not easy, getting the dinghy on to a rolling boat, and all alone. Lucky, I didn't go for a swim in the process.

My Internet Cafe on the beach.

The La Karz du Douanier Restruanrt, made famious by the tv series "Death in Paradize."

Happy tio be back out at sea, the dinghy securly attached to the foredeck.

The sail north to Antigua was delightful. I watched the sun set behind Monterrat, and entered Five Islands Bay in the dark, 8 PM. The Dove came to rest in 25 feet of water off the Hermitage Resort, where it was calm, no swells, an a gentle breeze. A rum and topic was issued to all hands. What a day!